One of the first poems I remember writing was a meager imitation of George Ella Lyon’s “Where I’m From.” It feels as though I was assigned to write a version of it every year of elementary and middle school (that and a version of the credo, the “I believe” poem – simple enough forms, lists that could be easily modeled, mad libs-style by eager-to-please 10-year olds). Though I was bookish then, poetry didn’t yet move me. My teachers, God bless them, were trying to tell me something about specificity, about terroir, the flavor imparted to a given creature based on where it’s sown. I filled in the assignment dutifully: I’m from yellow houses and red brick. I’m from Mary and John, from sweet tea and tacos, from Camp Street and Drewry Road. I hadn’t yet learned that, as the poet Mary Oliver once wrote, “Attention without feeling… is only a report.”

All of this is to say that though New Orleans and Houston get much more shine in my writing, in the 100-word biographies that live on my website or at the bottom of my articles, I am from Alabama as much as I am from anyplace. What I mean is that this is the land to which my ancestors were brought as property, where generations of us, Tuckers and Marshalls, Robbinses and Abneys, chose to stay, to build lives and families though the trees bore strange fruit. I’m from the plot of red dirt where the Abneys are buried, the land old man Jim bought so his descendants, those he once legally owned, could be buried together. And because of those things, because of what we’ve built here, at some point I decided1 that though 23&Me might trace my ancestry to Nigeria or Ghana (or England or Scotland), this is where I’m from.

This week I’m back in the 251, the land of good food and too many prisons (to borrow a phrase from Louisiana-born poet Jericho Brown). I’m here to visit my grandmother, who, at 97, is experiencing the kind of memory loss that is not uncommon for someone of her age but still pains me. She was an English teacher, and books have long been our common parlance. She’s been reading a lot of historical fiction, so I brought her a galley of Percival Everett’s James that I picked up at a work conference. The usual easy back-and-forth of our conversation is bruised, tender to the touch each time she asks me the same question I answered the day before.

I’m from magnolia trees and azalea bushes. My aunt, also a writer, once wrote that the Deep South calls to her “as surely as sweet honeysuckle calls to hummingbirds.” I was in San Diego a couple of weeks back and was astounded that magnolias can grow outside of the South, though they flourish in tropical and subtropical regions of all kinds, on this continent and elsewhere. The magnolia flower, the shared state flower of Louisiana and Missisippi, greeted me as a kid when we crossed state lines on I-10 on the way to see my grandma. The house where my mother was born, where my grandmother lived when I was little, had a big magnolia tree out in the front yard, and though the tree is no longer, I can still feel their petals, velvety-soft in my hands.

I’m from women who do not like to cook but still make a mean mac and cheese (and when I say mac and cheese I mean Southern-style, baked, bread crumbs and two types of cheese). I’m told my great-grandmother Irene, for whom I am named, was a hell of a cook (her tea cakes are discussed in hushed, reverential tones). The talent (and the affinity for cooking) skipped a generation, lodging itself in me and my Uncle Kevin instead. I’ve had an appetite for soul food since I was little, butter beans and cornbread and catfish and collards, which led an aunt to speculate that perhaps my name was more than a mere honoring of my ancestor but perhaps a portend that I had been here before.

I’m from brainy women, stubborn, smart, chatty women, women who talk back. I’m from a woman who had to leave. My mother began to dream of being an architect in the house built by her father on Drewry Road. It was a run-of-the-mill brick ranch, but it gave her the security she needed to dream big. When she was ten, she and her father designed a treehouse together, without nails, she tells me, so I’ll appreciate their prodigious feat. My mother grew up the daughter of a principal and an English teacher in the midst of integration, where her creativity was encouraged by her family though stunted by sheer isolation and segregation. In school, she was bullied for her idiosyncrasies, her proclivity for vintage fashions — she once threw a 1950s sock hop themed birthday party to which no one showed. I’m from women who wanted things that Black girls weren’t supposed to want.

I’m from a town that bears the scars of industry and subsequent disinvestment. Though I often talk about Katrina as my villain origin story in environmental justice, long before I was born, Monroeville was home to the Vanity Fair Dye and Finishing Facility. It’s hard to draw neat lines of causation, but my grandmother has always believed there was something in the water, something from the plant, something that killed her husband, my grandfather, of colon cancer, when her children were still in college. But though we bore the costs, the plants brought jobs, college educations, a populace interested in live theater, museums, the arts. Now, with the VF long shuttered, even the Winn Dixie has been closed since the beginning of the pandemic. Each time I come for a visit, the highway into town bears more and more empty storefronts.

When I was a teenager, I made a poster out of an old nautical map of Manhattan and some felt letters that read: “I was born very far from where I’m supposed to be, so I guess I’m on my way home.” And though that may have been true for 17-year-old me (bless their heart), I do think, whether I’ve been reborn or not, part of me belongs here on the red dirt.

Missed me?

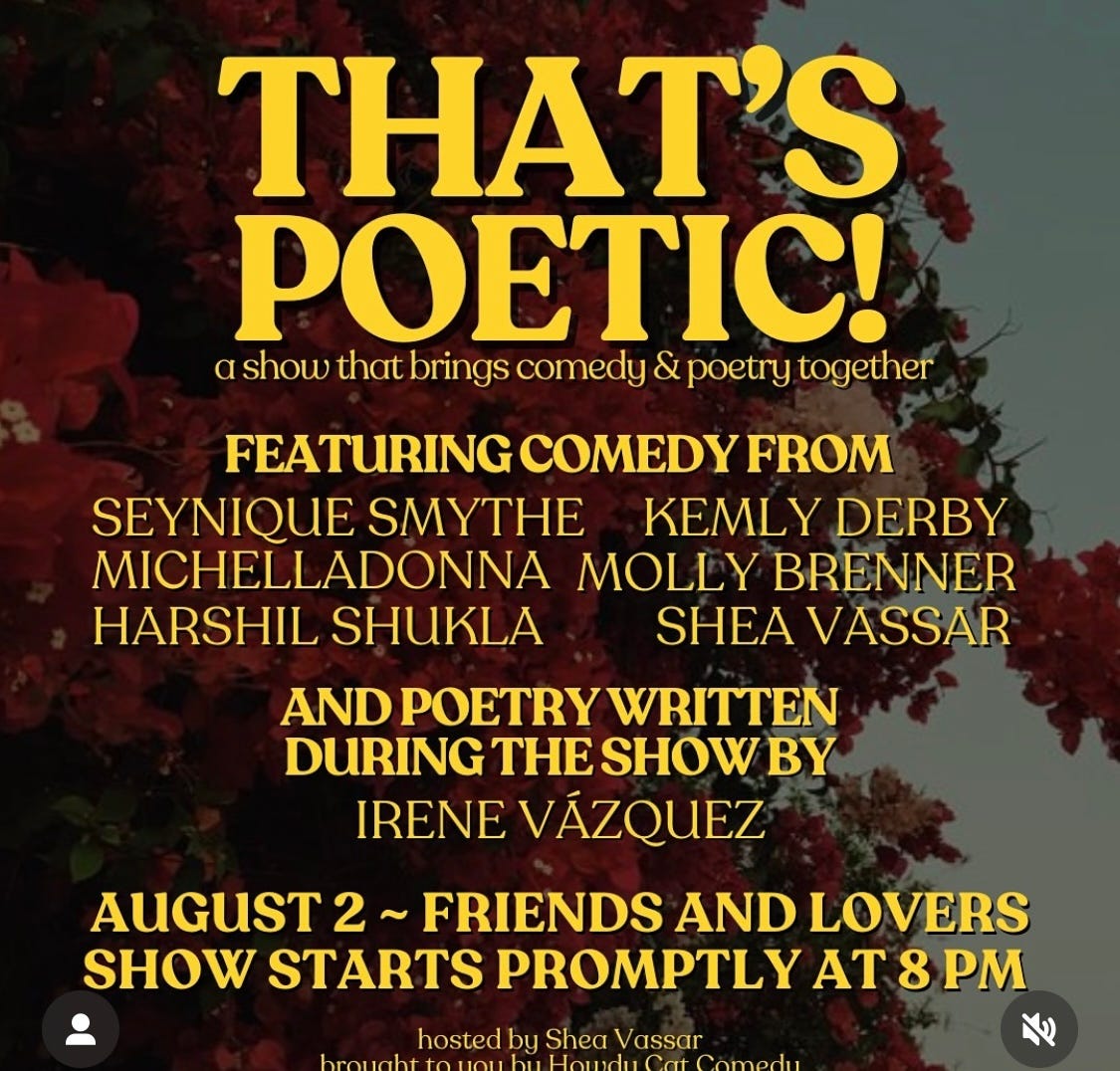

Somehow I added *even more* shows in August.

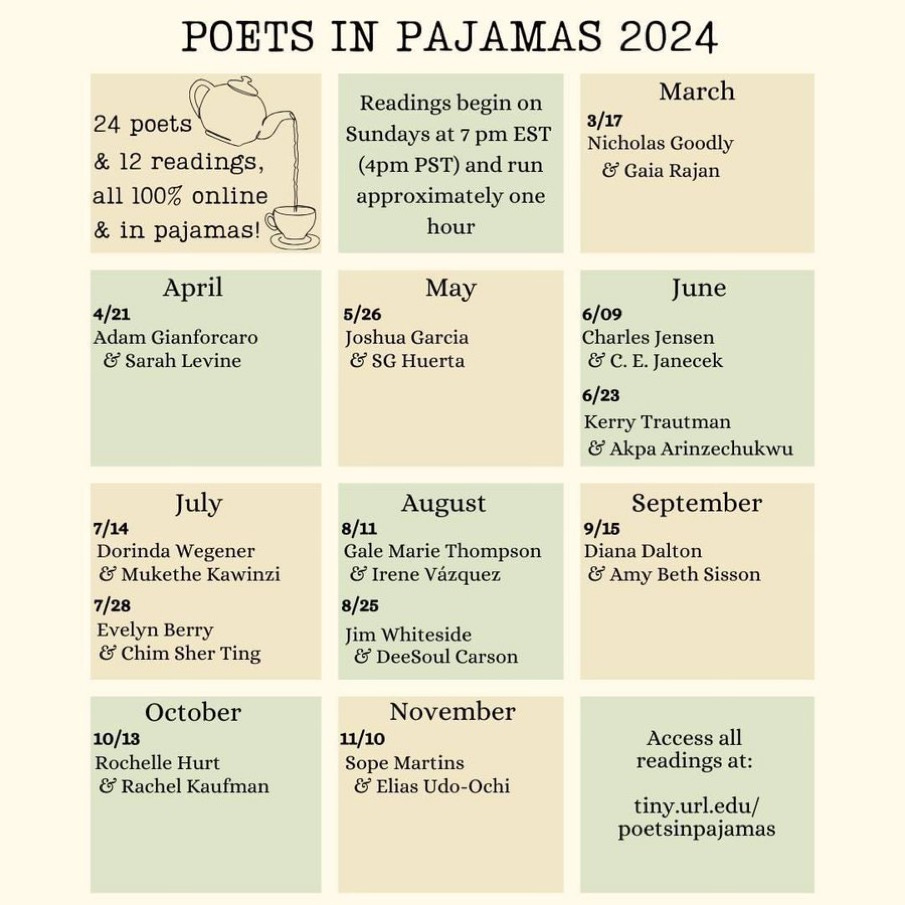

I’ve been told the Poets in Pajamas link didn’t work, so here it is - virtual!

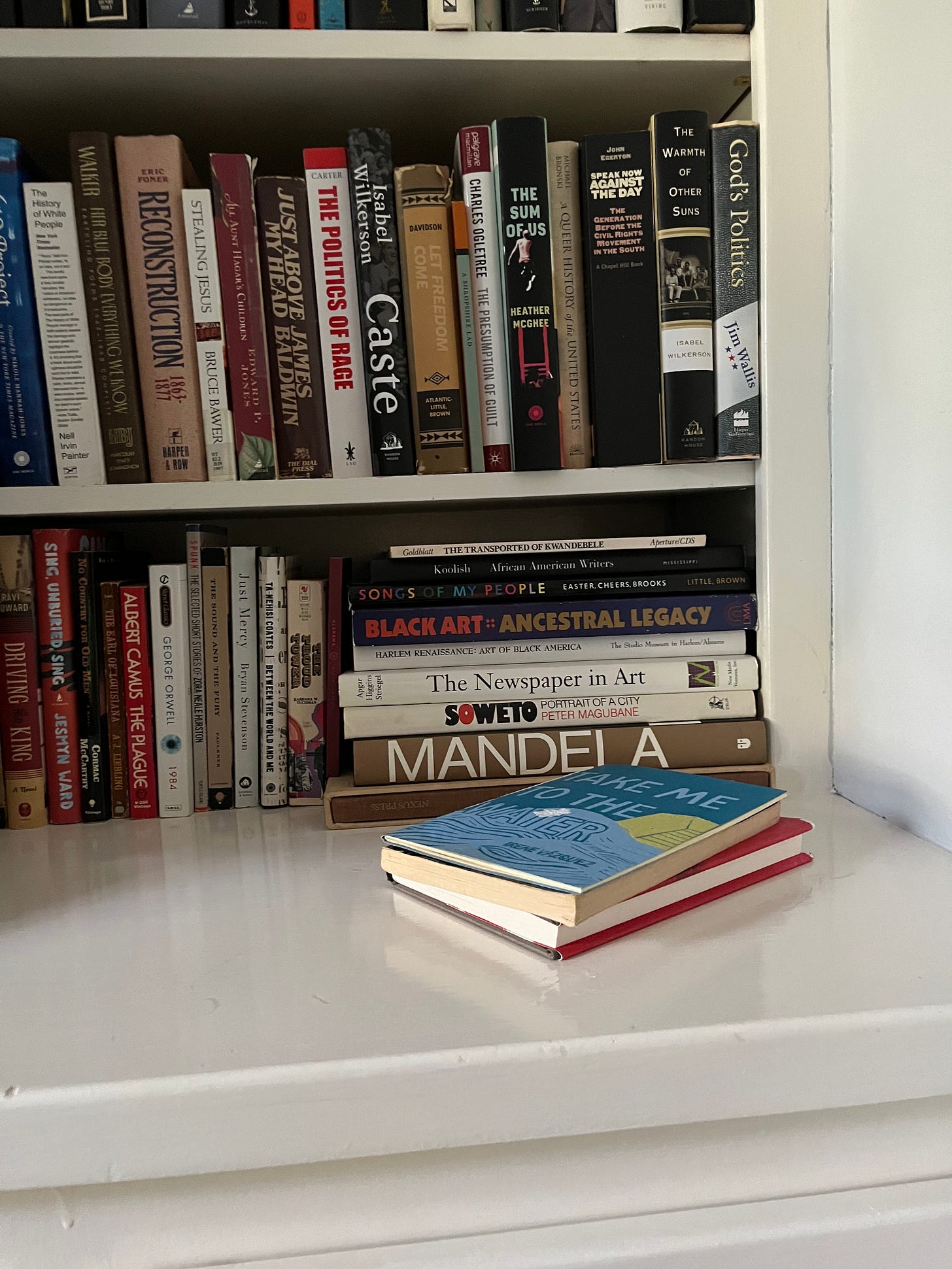

Currently reading: Grief is For People by Sloane Crosley

Spinning: “Backseat ft. Carly Rae Jepsen” by Charli XCX

My feelings about the nature of American Blackness, what was lost and born through the violence of the Middle Passage and the subsequent creation of Black racialization and the hyphen of African-America is the undercurrent of all of this, of course. But that’s a longer essay for another time.